Body Language Across Borders and Time Zones

“The truth is even though I’ve done an awful lot of zooming, it’s different because you don’t get the vibes.” Madeleine Albright, May 2020

I’ve worked remotely for the best part of a decade. Now that so many organisations have shifted to remote working and organising, I could share tips with you on how to facilitate an online meeting, or how best to set up your Slack channels. But honestly, we need to throw all the remote working ‘best practice’ rules out the window. If everyone started to work like I have been over the past seven years, it wouldn’t be a good thing.

Still, since remote working is here to stay, we have to figure out what does work. It’s not just the current pandemic — the shift towards online as well as offline action, the global nature of so many of the issues our organisations and movements tackle, the impact of border restrictions and immigration controls, and the improvement of the tools and technology that support remote coordination mean that this way of working is often standard and frequently the only option.

Why Zoom is exhausting

It’s having an impact on us. There is evidence that virtual ways of working are only entrenching inequalities and disparities within a group. Black and Indigenous people, other people of colour, and women, trans and non-binary people are talked over or sit silently, unable to get a word in. Differences in our housing situations and economic realities are exposed to each other through our Zoom backgrounds. Those with care-taking responsibilities, often women and lower income people, are having to contend with multiple, impossible demands at the same time.

Holding a marginalised identity is tiring in itself. On top of that, Zoom fatigue is real. There have been stretches over the past few years where I have felt delirious with exhaustion after sitting on 7–8 hours of video calls a day. Trying to explain the effect this way of working had on me to friends who didn’t work remotely used to be an isolating experience. I had the luxury of working from home and it didn’t sound too difficult — I felt I had no right to complain. So it’s been extremely validating during lockdown to see so many others describe their own feelings of tiredness and brain fog from being on hours and hours of Zoom calls.

The root causes of this fatigue are many and various. It’s harder to read social cues when you are looking at lots of faces at the same time. You have to exercise more of your judgement about when to speak up and when to keep quiet. You are likely sitting in a fixed position and less likely to relax in your chair and move when you need to. Your eyes are fixed several inches in front of you rather than moving to near, far, and back again. But I believe there is one reason above all that makes video calls tiring, and it’s that the experience shifts us into a trauma response.

In order to feel safe in the world, experience connection, and build trusting relationships, humans need co-regulation (read about Dr Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory for more information). Co-regulation is the process of two or more nervous systems attuning to each other and becoming calm through eye contact, positive facial and vocal expression, and sensitivity and responsiveness. We all know how this feels. When we are with someone we feel safe with, our breath and heart rate slows, our muscles relax, it’s easier to listen and we are quicker to smile.

Dysregulation is what happens with reduced eye contact, negative facial and vocal expression, insensitivity and lack of responsiveness. We know too well what this feels like. Our breath and heart rate quickens, our muscles tense, we are caught in our own story of wondering what is going on with the other person and are less able to listen and respond.

Video calls, and remote working in general, are built for nervous system dysregulation. We’re never quite looking each other in the eye. The camera is constantly freezing. Our voices lag or speed up, are unnecessarily loud or quiet. People’s facial expressions slacken while they check emails at the same time. Hands are out of sight while we take notes. Strange noises abound and we can’t be sure which square it’s coming from. Our nervous system response is mostly unconscious, so whatever our collective conscious intentions are, they do not make much of a difference. Our bodies on a fundamental level do not feel safe with each other. We can come off a call and wonder ‘am I the only one who thinks that was a complete waste of time?’ or ‘did the thing I just said land totally wrong?’ and have no idea as to the answer.

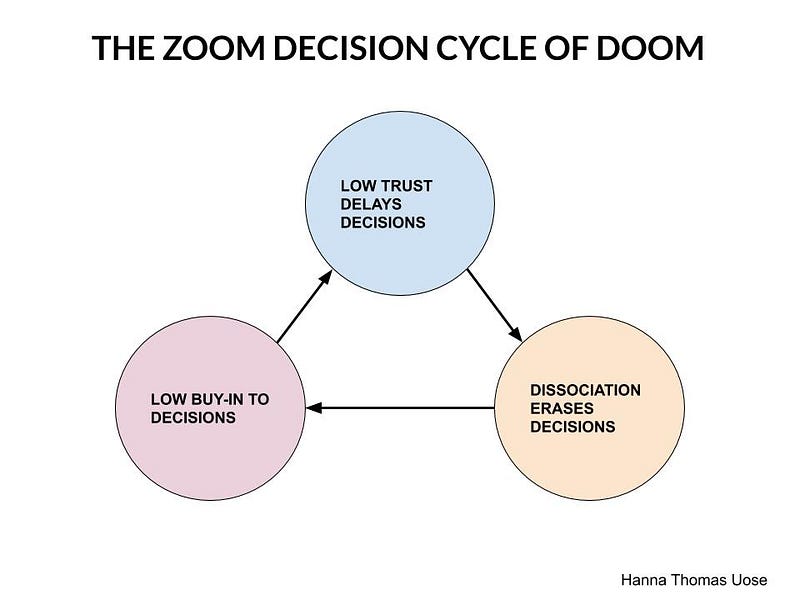

The Zoom decision cycle of doom

Calling it Zoom fatigue does not go far enough. The impact of working in this way is not just that we feel tired but that we are sitting in a low level trauma response for hours at a time. The impact is low trust relationships and a loss of memory associated with trauma and dissociation — I believe both of these effects deeply impact our collective ability to make decisions and to move forward.

If it’s harder to come to decisions because of low trust, and it’s harder to remember decisions because of collective dissociation, then it’s harder to get real buy-in on any decision by a group working or organising remotely. It becomes a self-fulfilling cycle that results in unhappy staff and volunteers and a massive slow down of the organisation’s likelihood of achieving its mission.

As Jenny Odell says in her book about the attention economy, How to Do Nothing, “A social body that can’t concentrate or communicate with itself is like a person who can’t think and act.”

Want to read this story later? Save it in Journal.

So what can we do about this? We cannot possibly settle for the current situation, or train others in how to adapt to it either. There is too much at stake. Organisers working for racial equity, climate justice and gender equality have gained too much ground over the past months and years to see their pace slow down now as a result of the global pandemic.

We can focus on building trust and connection, and give people more tools to document decisions, for sure. Some of this is easy to implement — if you’re not currently taking notes and making them easily accessible during your meetings, start doing that now. We can also build ritual into our collective practices. The Sacred Design Lab lights a candle together to anchor themselves in physical space even as they meet remotely. Taking collective breaths together can help ground us in our bodies and regulate our nervous system responses.

But I think we can go much, much further than this, and that this moment requires us to think more inventively.

If I can’t dance…

We think of Zoom as the tool we are using for remote connection, but that isn’t the only tool at our disposal — our bodies are the other. Except we don’t use our bodies to their greatest potential when remote organising, we pretend that Zoom is a replacement for in-person meetings and sit politely at our desks. The result is absurd. Rather than replicate the feeling of being together IRL, we transmute into a grid of floating heads, further alienating ourselves from each other.

So my question is this — how can we use our whole bodies to build trust and connection even when Zooming? Firstly, we could look to those who engage their whole bodies to communicate across distance — actors and dancers. They are trained to be hyper aware of what their bodies are communicating, using every inch of themselves to convey their inner life and be understood. Gestures and facial expressions are specific and heightened, often leading to the development of a whole new language of expressions as in ballet, breakdance, or kabuki.

You may think I’ve gone off the deep end but I keep wondering — what if remote organising doesn’t require less of our bodies, but much, much more? What’s to stop us from developing a more outré body language for remote working?

We already use some forms of stylised gesture for remote communication. One is emojis, a visual language that evolved to fill the gap when our voices and bodies are absent. Faces, hands, and hearts are the most popular emojis — we reassert our capacity for human connection again and again when we tap them out. The other one is consensus decision making. Many of us who have participated in activist meetings or attended protests will have twinkled our fingers in agreement or embodied a human microphone to pass a message on.

I know video calls feel different. I know it’s hard enough to get people to do a five minute icebreaker, let alone feel comfortable inventing a whole new body language for this purpose. I am under no illusions that we will change this overnight. But right now, we need to reckon with the fact that video communication is not real life. It does us and our missions a disservice to even pretend that it is, with devastating impacts to the day-to-day running of our groups and organisations, and to our overall ability to achieve our missions.

Let’s imagine. What if, 10–20 years from now, it was quite normal to be organising remotely (whether via video call or hologram..) and using our whole bodies?

I’m going to take some inspiration from a recent music video made on Zoom during lockdown by Thao & the Get Down Stay Down.

What if this was what ‘I love what you’re saying’ looked like?

What if this was what a ‘I have a question’ looked like?

What if this was what it looked like when a remote group landed on a decision?

What if this was what it looked like when a distributed coalition came together in strategy? (It’s actually a group of Juilliard students performing the Boléro)

Following this path means centering the voices and perspectives of those who have been living, working and organising like this for years either out of choice or necessity — neurodivergent people, disabled people, and people from cultures who are more bodily expressive and less uptight than the British one I am writing from. It means recognising that our bodies have limits and are constituted differently and that we need to create languages and alternatives that work for everyone so as not to replicate current inequities.

I wonder what the impact would be of centering these voices, experimenting with new ways of working and communicating with each other, and embodying our discussions while on calls. Whether it would keep us from moving into a trauma response of fight, flight, or freeze. Whether it would result in us being more in tune with our contributions and decisions. Whether we would better remember the conversation and the outcome. Whether we could collectively move into valuing multiple ways of being and knowing and away from the professionalisation and intellectualisation of NGOs that further disenfranchises marginalised voices. How our work would change, when we are fully engaged in each other’s humanity.

These wonderings are directly inspired by the work of groups like The Strozzi Institute, generative somatics and Forward Stance, who work with individuals and groups at the intersection of embodied leadership, healing, and social justice. By considering this work through the lens of remote technology, I hope we can radically change the way distributed groups and organisations operate too.

I don’t know what the end point looks like, or what the journey is to get there but I’m excited about the possibilities. If you’re interested in these questions too, I’d love to imagine and experiment together. Who’s in? Email me at hanna@wealign.net.

📝 Save this story in Journal.

👩💻 Wake up every Sunday morning to the week’s most noteworthy stories in Tech waiting in your inbox. Read the Noteworthy in Tech newsletter.