What story does your organisational structure tell?

One of my favourite, recent projects has been working with MAIA, a Black and women-led organisation in Birmingham, UK, focused on supporting artists and challenging systemic injustice. Mid-pandemic and mid-winter, the two co-founders Amahra Spence and Amber Caldwell asked me to help them clarify their roles and define the future structure of the organisation.

They were each personally struggling with the notion of being a ‘boss’ and the potential harm that can be caused by holding power over others. They had an aversion to being too direct with their small team, focusing on their deeply-held values of nurturance and autonomy — to the extent that the team sometimes didn’t know what their priorities were or how they would be held accountable.

The questions Amber and Amahra were grappling with are common within progressive organisations. Is the organisation an instrument for achievement or is it a location of liberation? Should we be taking lessons from corporate start-ups, or should we rather replicate the communal, consensus-driven approach not usually seen outside of (healthy) family structures or intentional communities?

These questions and conversations are crucial, but it’s telling that they arise most often when the people involved are not in agreement around mission, vision, and values. What started out as a question of structure and roles quickly morphed into an exploration of MAIA’s identity. Who are we? How should we be?

I interviewed the team one by one to get a better sense of the dynamics. While it was clear that each person described the mission and vision of MAIA slightly differently, what each had in common was the way they spoke about MAIA. They talked of serving MAIA. They talked in heart-centred, spiritual terms, bringing in metaphorical language — MAIA was a tree growing its roots in the soil, MAIA was a young mother providing sustenance. In Ancient Greek myth, Maia was the mother of Hermes, goddess of nursing mothers. In Roman religion she became known as an Earth goddess, of springtime, warmth and increase. The month of May is named after her.

The poetry of these interviews gave me pause. Rather than defaulting to my regular problem-solving brain, asking myself what these two co-founders should do with MAIA, I gave myself permission to follow the team’s lead. What should MAIA — the mother, the tree, the goddess — do with them? If the organisation has a spirit, what does it want and need from the team?

There is a long tradition of flipping the script like this and listening to the point of view of the mission itself. One suggested exercise for this is called The Empty Chair from Frédéric Laloux’s book Reinventing Organizations.

“A simple practice to listen in to an organization’s purpose consists of allocating an empty chair at every meeting to represent the organization and its evolutionary purpose. Anybody participating in the meeting can, at any time, change seats, to listen to and become the voice of the organization. Here are some questions one might tune into while sitting in that chair: have the decisions and the discussion served you (the organization) well? How are you at the end of this meeting? What stands out to you from today’s meeting? In what direction do you want to go? At what speed? Are we being bold enough? Too bold? Is there something else that needs to be said or discussed?”

You can take this approach even further. You can consider that you are in a symbiotic relationship with your organisation; that the organisation is an entity with its own wants and needs. You can even read your organisation’s astrological birth chart for guidance (idea copped from Decolonising Economics). By sitting with this point of view, the next step towards transformational change, both internally and out in the world, can become clear.

In our project, we used guided imagery techniques in workshop with the whole team to ‘listen in’ to MAIA and develop a new mission statement that felt true to what the organisation had become. It reads:

MAIA is an arts and social justice organisation. Our vision is a world where artists are seen as powerful decision-makers in how structures and systems work, and where the manifestations of systemic change are recognised as art. Our mission is to redefine what it means to be an artist, challenge who gets to make their dreams real, and invest in the transformative possibilities of the Black imagination. Our projects serve artists that the system doesn’t serve (including those who do not yet define as artists) by designing and developing spaces for liberation, redistributing resources, and providing creative programming. Our work is done in community and informed by our four core values of joy, care, access, and justice.

We answered the questions around ‘what’ and ‘who’ with this statement. But the ‘how’ was still missing. I kept thinking of one of the rules of Benedictine monastic life, which is to ‘keep death daily before your eyes’ in order to remain focused and present to what really matters. How could those participating in MAIA’s organisational life ‘keep mission & vision daily before our eyes’? How could MAIA keep the mission and vision ‘alive’ for the whole team as they moved into their next season of programming, without putting the onus on one or two people who were more interested in sharing responsibility than accruing it?

Thankfully, it was easy to dream together with the team, a group of talented, embodied artists who thought laterally. Together, we wondered if the spirit of MAIA could be represented in the very structure of the organisation, and whether that might support a daily practice of mission-driven strategic thinking. Could that structure help the team to think about hierarchy and accountability differently too?

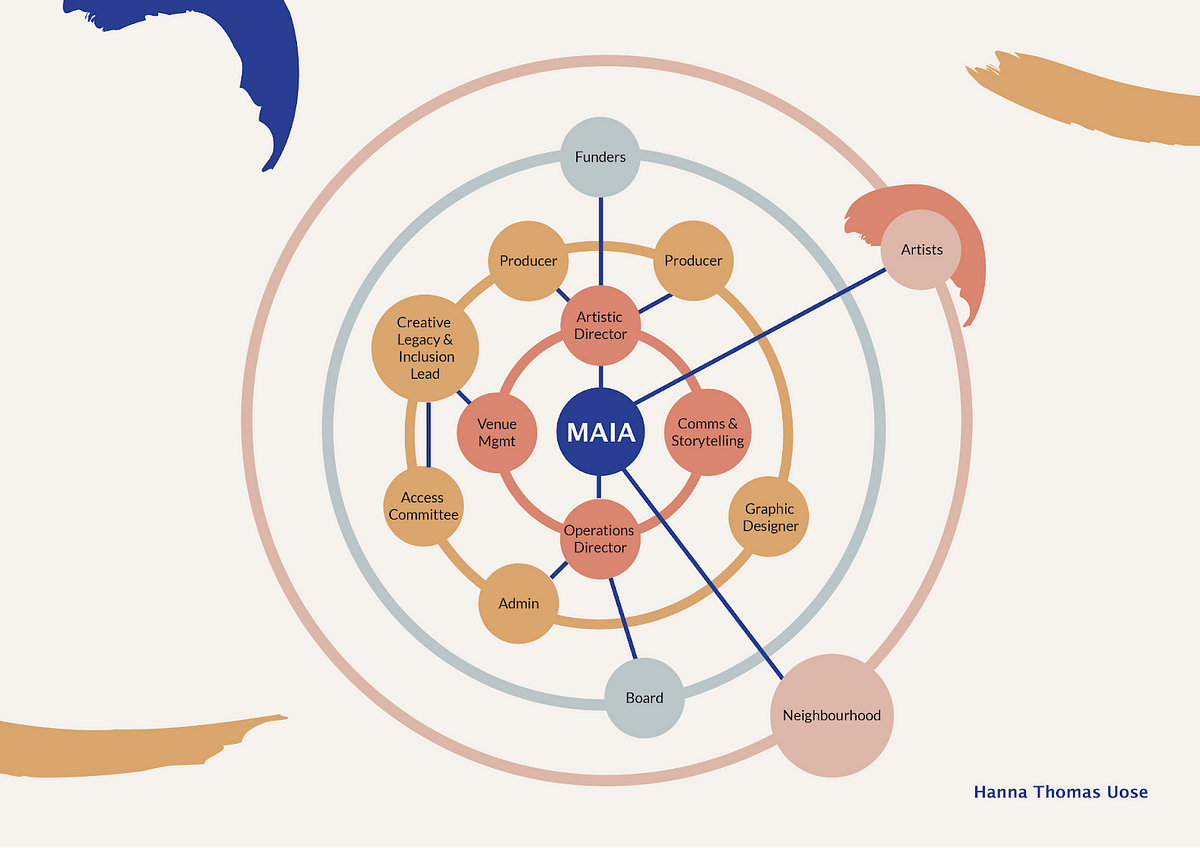

Here’s the first draft of an organisational chart I came up with for MAIA, which places Maia the tree, the young mother, the goddess, at its centre (the chart is notional and pulled from my own head, rather than accurately representing all of the different relationships between the team and their surrounding communities):

Each circle represents an increasing proximity to the spirit, mission and vision of MAIA herself, instead of any ‘boss’, reframing how power is seen within the organisation. That doesn’t mean that there is an absence of responsibility — the more key the role is to upholding the mission and vision, the more power the role has. The structure reminds us, too, that our accountability in movement work is to mission and vision always — not to any individual who happens to hold a particular title.

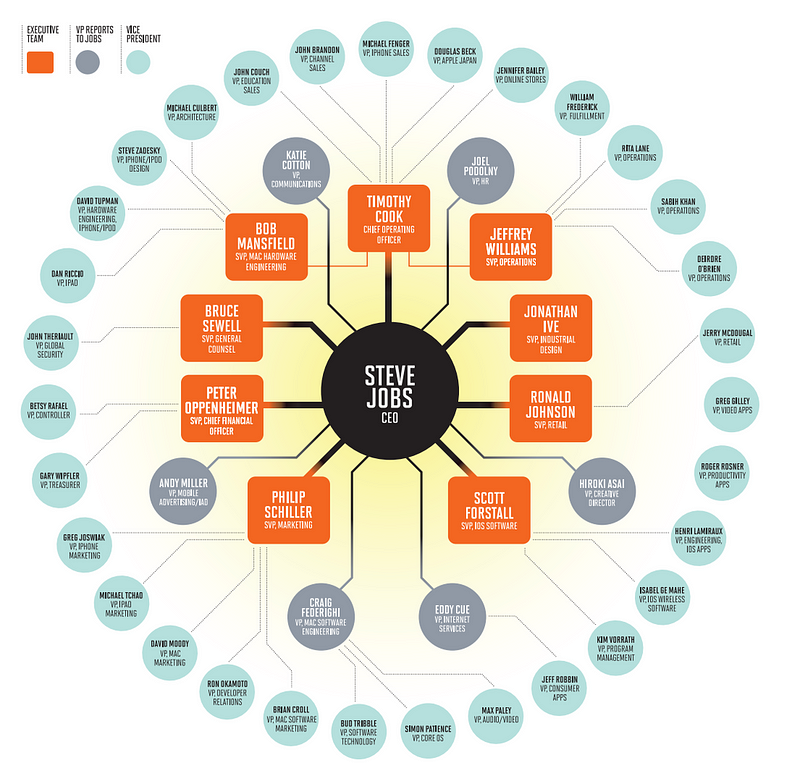

This line of thought did, however, give me pause. Perhaps it was too cult-y / weird / woo-woo (delete as appropriate) to make sense as an organisational structure. So, I researched other examples of circular structures and came across this one from Apple, when Steve Jobs was at the helm. I needn’t have worried — since a cult is more often focused around a particular person than a set of beliefs, Apple’s structure here is closer to a cult than anything I could think up.

What would have happened, I wonder, if Apple’s organisational structure had told a different story, if it had placed mission or metaphor at the heart of its structure rather than one individual? Perhaps Steve Jobs wouldn’t have been so lionised, or his successor Tim Cook so maligned in the years since. Perhaps paying attention to the story that Apple’s organisational structure told could have been an act of preservation and sensible succession-planning.

I’m not suggesting that this approach — putting the organisation itself at the centre of the organisational chart — is right for every organisation. With MAIA, we’re still delving into the work and figuring out where they want to go. But I am suggesting that every organisation could spend more time thinking about what stories their current structures are telling.

What is an organisational chart or structure anyway, apart from a story that we tell ourselves about who gets to make what decision, what salary people take home, and what they have their eyes on day-to-day? What other stories might progressive organisations want to embody in their structures and processes in order to be more in step, and more impactful?

As a writer, I often think about what organising principles my stories need, but that obscures the fact that story itself is an organising principle. It unites people behind a common cause. We need to tell ourselves who we are every day, over and over again, until we begin to believe it. Until our mission & vision lives ‘daily before our eyes.’